I don’t like my body. I never have. At least when I was a child my small and wiry clothes hanger-like frame adequately clothed my timid and anxious personality. Things changed in year five, though; seemingly overnight I developed rounded breasts, meaty thighs, and a greasy mop of hair. I felt like the human equivalent of some sort of boxed meal at KFC.

When my body began to bleed once a month, it repulsed me. When my body sprouted bristly pubic hair, it confused me. When my body produced a stench so strong that, one day, a classmate unashamedly muttered to my face, “You smell,” it embarrassed me. Above all, my body terrified me.

I was petrified because I was trapped in a fatty and bloodied lump of flesh, with hormones and cells that were transmogrifying beyond my control. They were going to keep going until they had matured into their final form: Adulthood. The thing is, I was ten. I wasn’t ready to be an adult. I played The Sims 2 after school and wrote quirky short stories about my cats. My body was developing at a rate faster than my mind, a fact that relatives reinforced by telling me that I was “Turning into a real woman!” and that I had “Grown so much!” They meant no harm and I knew that their words were steeped only in encouragement, but these affirmations still filled me with dread.

My curvaceous form meant that strangers showed me attention, too; men catcalled me on the street, barking at my “sexy legs” or “good tits.” I remember walking with my family through Perth CBD one weekend when an old man approached me and simply croaked: “You’re gorgeous, girl.” I was twelve. These behaviours are deplorable in any circumstance, but being sexualized at such a young age sickened me.

Health class never taught me how to remedy the thoughts of embarrassment, confusion, and shame that plagued me. Sure, I could insert a tampon and learnt the difference between the labia minora and the labia majora, but my mental health was suffering. My mind was a toxic cesspool, telling me that I was uglier (big nose!), fatter (huge stomach!), and denser (shit at mathematics!) than my classmates. I persuaded myself that this, surely, made me a worthless person; no amount of compassion or kindness could convince me otherwise.

I was diagnosed with anorexia nervosa at thirteen. The hospital became my home. For days at a time I was confined to bed rest; my body was too weak to move, and any physical exertion risked further weight loss. I sat in bed watching Nickelodeon with a nasogastric tube threaded through my nose that travelled down my throat and into my stomach, which secreted a high-calorie formula. It made me vomit violently. I either showered in a wheelchair, or with my mother by my side to ensure I didn’t fall because my blood pressure was so low. My hair fell out, I stopped menstruating, and my gums bled. I swallowed tiny pills to alleviate my intense melancholy.

My eating disorder only exacerbated my pernicious self-worth. My rotten psyche led me to believe that I was still ugly (deathlike pallor!), fat (two saggy teats!), and dense (failing school!). The difference this time, though, was that with a lot of love and patience, my condition gradually began to improve. This came from therapists, doctors, friends, and in particular, my family. They nurtured and supported me when I could not, and did not want to care for myself.

My family, ultimately, fuelled my recovery. They made me realize the magnitude of my actions. Anorexia made me selfish, bitter, and mean; I took virtue in hurting people because I wanted them to understand the pain I was going through. The severe depression and anxiety that accompanied it rendered me emotionally numb to these actions, as well any corporeal changes. I didn’t care that I was killing myself, and bringing those around me down, as well.

It was a culmination of several moments where I truly realized that my agony was manifesting within them. I overheard my mother weeping to my father about the persistent black cloud that loomed over her head. My sister broke down in tears when my parents told her that I had to reside in hospital indefinitely for suicidal thoughts. I saw my father cry for the first time ever in family therapy.

I have never suffered such immeasurable remorse and dejection as I did during this time. I still carry this guilt and sorrow deep in the pit of my stomach, with constant nausea a physical reminder of my past experiences.

I have tortured, starved, and harmed my body to – in some cases – irreparable extents. I have been told that my nausea will probably never go away, and I will need to be medicated for the rest of my life. I nearly broke the people I love more than anything else in this world. I have been in therapy for nearly 8 years. And you know what? I still don’t like my body.

I go through prolonged periods where I house a lot of self-hatred that morphs into a punishing internal monologue. Sometimes I force myself to skip meals. On occasion, I have “forgotten” to bring a coat in freezing conditions because I know that my body will burn calories trying to warm itself up. I suck my stomach in every single time I have sex so I appear thinner. I wish I did none of this.

It saddens me that I still allow thoughts of self-doubt to overshadow rationality. I know that what I do is unhealthy. Now, though, I have the tenacity to let my grievances only wound, rather than maim me. When a boy asked me for nudes and I declined his offer, he defiantly said: “You probably have pendulous, aubergine shaped breasts with areolae the size of saucers, anyway.” I cried for a bit. And then I laughed.

I am not here to give self-love advice akin to that in the Girlfriend Magazine sealed section. My experiences are wholly my own: If there is one thing I have learnt, though, it is to accept that even though I have a mental illness, my mental illness does not have me. My mental illness riddles me with guilt, but there is nothing shameful in having a mental illness. My mental illness can control my actions, but, ultimately, I control my mental illness.

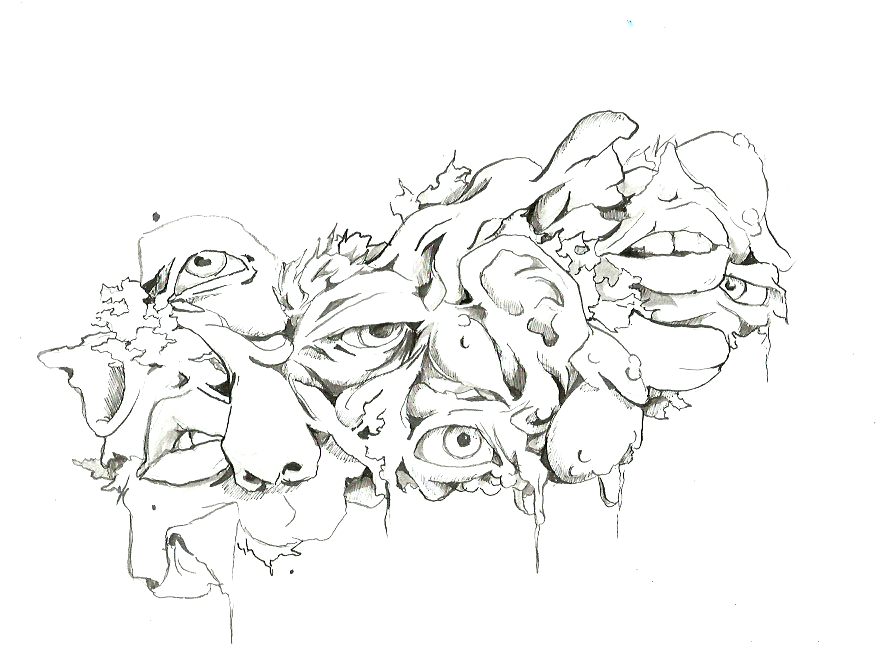

Words by Isabella Corbett, art by Lilli Foskett

This article first appeared in print volume 88 edition 5 HOME