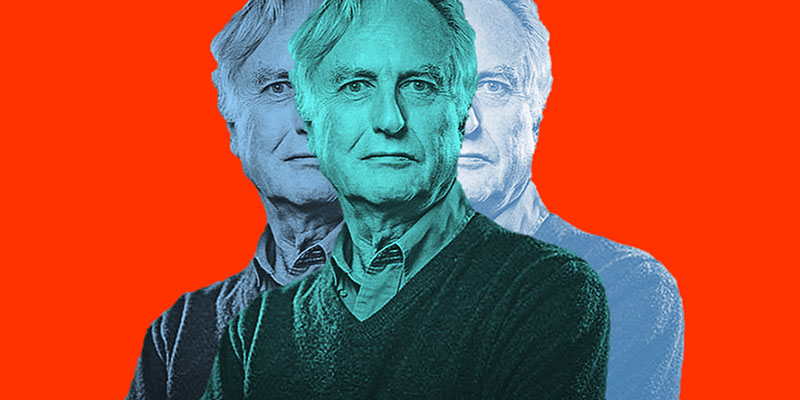

Perth turned out for a Monday night, welcoming Professor Richard Dawkins to the stage of Perth Convention & Exhibition Centre with rapturous applause.

Dawkins, hosted by John Safran, spoke on topics ranging from the evolutionary reasonings behind xenophobia to the evolutionary nature of memes between much laughter. The event didn’t bring fans much new knowledge, but rather treated them to exclusive readings from his newest book Science in the Soul, and his dry, warm, undeniably British sense of humour.

But contrary to the implication of the title, there was less talk of science than there was of the soul.

Dawkins is known for making bold, controversial statements surrounding religion, which he most definitely delivered. Among these were “Muslims are the greatest victims of Islam,” and “reading the Bible is the best cure for religion there is.”

Religion, he explained, is a framework upon which communities base their identities and legislation. It has no survival advantage but rather is a by-product of something that does.

Dawkins drew from his writings in his previous publication The God Delusion wherein he illustrates the flying of a moth into a candleflame. Celestial bodies at optimal infinity, such as the sun and moon, emit parallel light which is used by insects for directional guidance. This intrinsic survival instinct is present in moths. On the rare occasion that a moth should confuse a candleflame with the sun, their flight compasses mislead them straight down paths of suicide – the normally life-preserving habit, taken out of proper context, has the adverse effect.

Using this analogy, he defined religion as a consequence of misdirected rule-following. Parental guidance is beneficial for survival in most cases concerning child safety and welfare. But habits taught in childhood, namely blind unquestioning obedience (and the reward of it) squander the perceptible difference between commandments “don’t jump off a cliff” and “pray five times a day facing east” when spoken from mouths of authority.

Dawkins likened religion to computer viruses, propagated from one generation to the next, saying “everywhere in the world, people will believe different nonsense… it’s an amazing coincidence that everyone is born into the right religion”. He stated that “for people to label themselves with the religion of their parents is pernicious”, although it is not uncommon to find scientists using ‘God-language’ and attending Christmas sermons. Dawkins explained that while the likes of Einstein and the late Stephen Hawking spoke of God in their most famous quotes, examination of their real beliefs reveal them to be atheists who participated in religious rituals only for cultural reasons. Their use of ‘God’ and his use of ‘soul’ are similarly intentioned to convey the wonder of science and a deep emotional reaction to it, for which a secular word does not currently exist.

He proposed that essentialist mindsets cultivated by monotheist creationism is to blame for the public’s delay in acceptance of evolutionary theory. Essentialist mentalities promote the idea of absolute states of being rather than imperfect approximations of ever-changing organisms. While useful for distinguishing species, Dawkins believes unnecessary lines are drawn when it comes to stages of human life; of which he proposed a zygote is not the beginning, but rather the beginning of a gradual encroachment towards.

When prompted on Darwinism, he proposed that while explanatory of evolutionary truth, it cannot serve as a moral compass lest one surrender to “fascism gone native”. Natural selection is a brutal, shortsighted process, hence the idea of government by genes remains politically undesirable. Although one may virtuously raise a fist against it, it is futile to try distorting truth. Put eloquently by the man himself, “finding comfort in something doesn’t make it true. You can believe with unshakeable faith that the tiger that is chasing you is a rabbit. But it’s not. You are going to die and that’s it.”

Dawkins preached that science should be promoted with a sense of wonder instead of being ‘dumbed down’ to the aesthetic of the lay public. Although he’s published many bestsellers to date, he’s still not done, hoping to publish a children’s book titled ‘OMG I Think I’m An Atheist!’ which will educate rather than indoctrinate, and unapologetically “focus on the wonder of science, the horrors of the Bible, where morality comes from and teach children how to think for themselves.”

Following an open Q&A discussion with audience members, the world-renowned professor was shown offstage by a standing ovation.

He left the theatre echoing the reminder that with the nobility of human being comes the desire to discover; to expand with the universe our knowledge of it. On such a quest, “it is possible for the human mind to be split in an utterly ludicrous, barmy way,” as is most often the case as we continue to unfold and understand the world around us and our place in it.

Caitlin Owyong

Science Editor