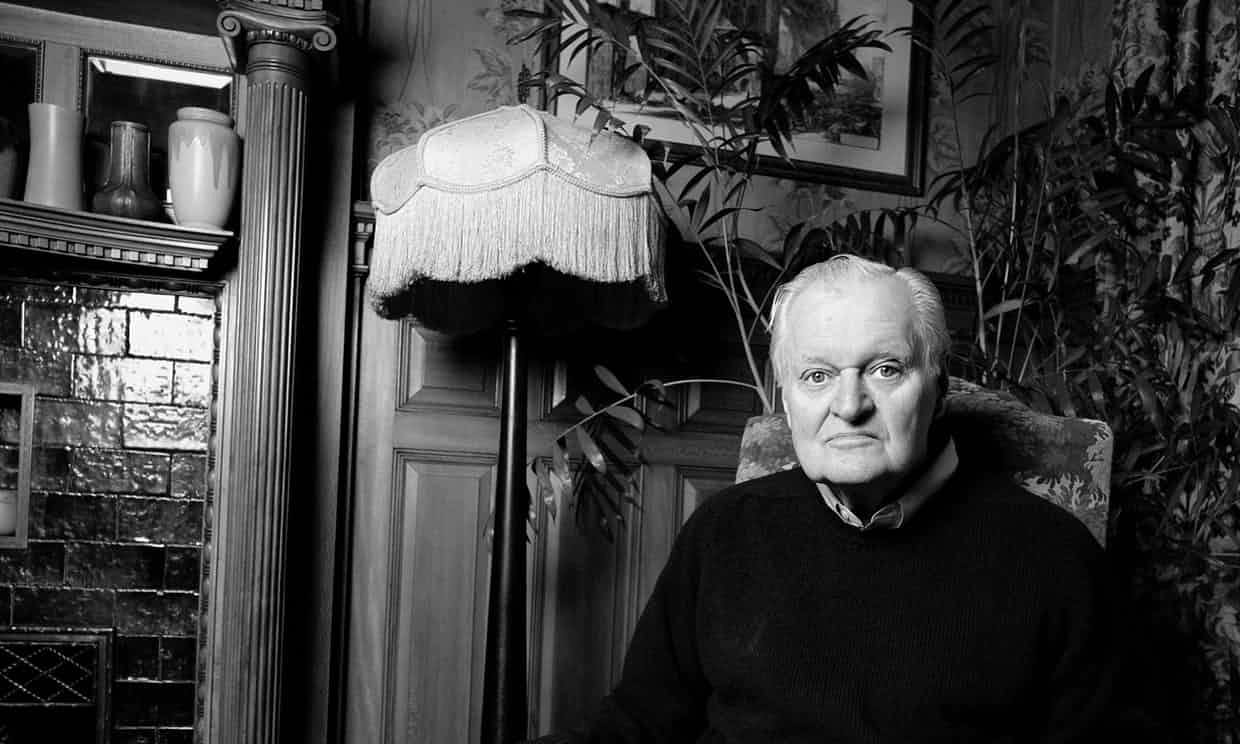

At 90, John Ashbery is dead. An unorthodox man, his poems have dominated the literary landscape for the last sixty years. In his increasingly abstract work he bore into modern language, and unquestionably reshaped contemporary poetry.

His success was achieved with the aid of a few important critics. Helen Vendler championed Ashbery throughout his career, viewing him as an heir to Wallace Stevens and Walt Whitman. In a few of her key books the American voice, Vendler assured his place at the fore of the nation’s Literary Canon. Harold Bloom, slightly less scientifically, was also a booming advocate of the New York poet. Bloom wrote: “No one now writing poems in the English language is likelier than Ashbery to survive the severe judgments of time.” Now we have the chance to see.

Ashbery began his career as a Harvard poet, before taking a scholarship in France and finding work as an art critic. His 1975 collection Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror won the Pulitzer prize for poetry, the National Book Critics Circle Award and the National Book Award, establishing him as among the most powerful of living writers.

Increasingly, the collection is overlooked in favour of his earlier and more accessible works such as ‘Some Trees’, but I believe it sums him up in a few key ways. His entry into abstraction is there in the words. The fact it is based around the 1574 Parmigianino painting shows a man bent on loving very old art in very new language. The American interest in European work is a self-aware nod to the cultural cringe, present in much of his poetry and criticism. The curving of the mirror is the mannerist distortion of the self. This gets at a self-abstracting otherness, which was at the core of Ashbery’s poetics for two reasons: because he was extremely well-educated, and because he was gay.

Combined, these qualities allowed him an insight into the multifaceted sexualities of modern experience, and an understanding of how we use language to express them. This made for enormously powerful poems. His volumes are full of verbal echoes, differing registers, oppositions, and mistakes. And really, this is because most of life is too.

Being so difficult, Ashbery is not without his detractors. Clive James said his later poems were plastic sludge, and many more dismiss his oeuvre as pretentious nonsense. And of course, it is. In a sense Ashbery was using the idea of garbled registers to parody the idea of communication, meaning nothing could ever really get through. He was rejecting the idea of direct statements, or at least purposeful ones. And yet, his poems are undoubtedly, and curiously, full of meaning. As Paul Muldoon said, they evoke the experience of experiencing things.

I am going to write a thesis on John Ashbery next year, because his poems have had a big effect on me. His longer poem ‘The Instruction Manual’ was one of first things I read at University, and I have revisited it very often since. Perhaps greedily, I had hoped that one day I might contact him, to ask some of the more pressing questions I have about his work. But it is silly to expect these poets to hang around, since dying is part of their art. As is written in ‘The Instruction Manual’: “What more is there to do, except stay? And that we cannot do”.

Words by Harry Peter Sanderson