My first interview is with a couple who I meet in a coffee store. They typically breakfast in Putney, but on this morning have decided to come further into the centre of the city. David works as an electrician, and supports Fulham. His wife Samantha (who I am invited to call Sam) is a town planner. They must both be around 50, David perhaps slightly older.

David tells me that he didn’t vote in the referendum, “but does have some views on the outcome”. I ask him to elaborate.

“As long as it’s run well, we’ll be alright, but I just don’t know if they have it in them. David [Cameron] seemed to be up to the job, but now he’s fallen off, I’m not sure who else can really see it through.” He sighs, and begins to read a large copy of The Times. I ask Sam her preference, and she tells me that like her husband, she did not vote. She also tell me they have a daughter around my age.

“Her name is Sophia!” she smiles. I don’t know how to respond. I ask David who he thinks will be the next Prime Minister.

“Boris has been around for a long time, and I think people trust him. It would be a shame to see him miss out. There’s worse people in politics. That Farage [here pronounced to rhyme with garage [rhymed with marriage, rather than mirage]] is a nasty piece of work.”

Not long after this conversation, on June 30, Boris Johnson surprised most by ruling himself out of the race for conservative party leadership. A few days later, Farage – the second, UKIP horseman – did so too.

“Sophia is about to begin studying medicine,” Samantha interjects, and this gets the better of me for a moment. Samantha must sense my brief pause, because she immediately pulls out her iPhone and starts showing me pictures of her daughter, who is objectively very good looking. By the third picture, it is clear she is in fact too good looking, and I try to distract Sam from showing me more photos by pushing on with talk of immigration.

“Well,” begins David, “it all seems to concern terrorism, but I don’t see how leaving the EU will stop that to any good extent. We need to focus on finding them where they live. The US seems to have that covered. We got that bin liner, didn’t we? Black bin liner?”

“Bin Laden,” Samantha offers, still looking down at her phone.

“Bin Laden. We got him, that was good. I think we need to keep hitting them there, rather than trying to stop them moving around Europe.” I’m about to pursue this further when Samantha remounts her offensive, shoving another photo of Sophia under my nose, this time standing in a garden holding a glass of champagne and wearing the most charming smile I have ever seen. I avert my eyes.

“We have friends who run a pub in Greece, but I think they’ll be able to move back and forth all right still,” muses David, crinkling his paper. “I’ll have to talk to them, though.”

“She starts study in September!” says Sam, brandishing more photos. I mumble that one year ago I dated a girl who went on to study medicine, but I don’t think she hears me, and I look down into my coffee. “She is single, too!”

I make one last attempt at keeping the conversation on track: “Won’t it be more difficult for her to move around Europe if she wants to study abroad in, say, the Netherlands, or Austria?”

“Oh, I don’t know – I don’t think so. Would you like to know her Facebook address? I’m sure she could send it to me.”

I consider, but ultimately decline, and say a hurried goodbye. I walk down the street, next to a park, and see a man painted in blue protesting the BREXIT result. While this might seem just the person to speak to, I am not yet fully awake, and decide conversing with him would probably be too much of a trial, since he looks to be passionate and outspoken. Besides, his face-paint marks an agenda, and I’m here to speak to the ‘common person’.

The day is hot, and I stop to by an ice-cream cone from a vendor by the park. I take Bavarian chocolate, and continue walking. Minutes later I am solicited by a man pedalling church pamphlets and bibles, and wearing a green shirt with black lettering that reads ‘THE END IS NEAR’. He is well-spoken, and tells me he is originally from Wales. I ask him about the BREXIT result and, like David, he didn’t vote, but thinks Britain should have REMAINed. He is careful to footnote this opinion with the point that it doesn’t matter anyway. Imperceptive, I ask why, and he reminds me that because of overwhelming human sin and growing spiritual indifference, Everything is coming to an End. I ask him if this is the case for London exclusively, and he tells me it will be the whole world.

“For the whole of Europe, then?”

“Yes.”

“Croatia?”

“Yes.”

“Estonia?”

“Yes.”

“Luxembourg?”

He nods quickly and furrows his brow: “Oh yes.”

“Slovakia and Slovenia?”

“Yes.”

This is all a bit much. I take one of his bibles and he smiles.

“Stay awake!” he commands. “And enjoy that ice-cream!”

I do.

I continue walking, and pass through some Botanical Gardens. There is a girl on a white wooden bench reading A Wanderer Plays on Muted String by Knut Hamsun. She looks Spanish, or perhaps Maltese. I later find out she is of Portuguese descent, though born and raised in Britain. We talk for some time. She is studying Psychology and Law, and we share an appreciation for the colder British climate. Glad to get a student’s perspective, I broach the subject of BREXIT after an appropriate amount of small talk.

“To me, it all comes down to immigration, which is why I voted LEAVE. People don’t see it, but the

EU is incredibly weak right now. There’s too much ease of movement.”

I express some concern as to the situation of the eastern asylum seekers, which evokes very little pathos.

“Of course we should let some of them in if they legitimately need help, but we do need to be more careful. Many if not most of them don’t want to participate in our society. Once they’re here, they don’t do anything. They won’t integrate, and it becomes dangerous.”

“Oh.”

“It’s exactly what happened in Rome – Valens let the Visigoths in, they didn’t want to conform to the ethical standards of the Roman people, and they ended up burning the place to the ground.”

“Um –”

“The worst part is, you’re not really allowed to say any of this. Have you read any Brendan O’Neill?”

“No,” I lie.

“He’s excellent.”

I shift the conversation to talk of the horse-drawn carriages which follow in a procession around the gardens, mostly carrying tourists. The horses all look at the ground while they plod along, but don’t seem unhappy. Farther away, one has broken off from the path and walked across the grass, where it now slowly circles a great bronze statue of Winston Churchill. Its driver pulls at the reigns furiously to try and get it back on track, to no avail.

“Lots of horses in Dublin,” I say, in order to keep the conversation going. I don’t think she hears me, though, because she’s still concerned about immigration.

“Have you seen any speeches by Milo Yiannopoulos?” she asks.

“I don’t think so,” I lie.

“You really should.”

“I will,” I lie again, and reflect that she is one of my least-favourite people. I think of telling her that one year ago I dated a girl who went on to study medicine, to perhaps impress her, but decide against it.

“How is the book?” I ask.

“Hmm?”

I point to the book in her hands.

“Oh,” she looks down, “yes.”

My next interview is with an elderly Swedish lady named Gretta, who reminds me of my own grandmother, and is one of the most excellent human beings I have ever met. I find myself sitting near her table at lunch, and since I don’t think she will respond well to immediate political talk I begin by showing her pictures of my new niece and nephew, who she thinks are equally “very plump”. Ice broken, I steer the conversation sharply and surely towards BREXIT. Gretta and her husband (who was sitting next to her at the table, but remained silent the whole interview, in part I think because he did not speak very good English – he was Finnish – but whom seemed amiable and well-groomed, and whom I trusted because of his connection to Gretta) had become citizens years earlier, and had voted REMAIN.

“It seemed a bit sensible, and it is what the young people wanted. Scandinavia is good outside of the EU, but it is a very different places, with very different economies. I do not think this will be a good idea for England, no.”

These words are spoken warmly, and with thought. It was only in hearing them that I realised all my previous interviewees – David and Samantha, the bible salesman, the garden student – had seemed to circle around their conclusions when they spoke, as if being pulled into some invisible centre. Gretta was far more direct.

She continued: “I think the people who wanted to LEAVE do not know what they are going to do now.” The conversation drifts to other things. We both believe Copenhagen to be the greatest city in the world. She enjoys Belgian beer, is sympathetic to the Syrian cause, and asserts Italian people are, on average, too loud. Romanian shortbread is an underrated delicacy, suicide rates are too high in Hungary, and Boris Johnson is “a very dangerous man indeed”.

“Europe must be kept open, because it is a place of openness. It is about freedom and leisure. This–” she spread out her arms “–is the way you should be living at your age. In restaurants, surrounded by academics and merrymakers, activity and conversation. Drinking champagne and listening to music!”

We were the only three people in the cafe, and it was almost completely silent.

That night, I find myself standing outside a bar in east London, listening to Allen, an investment banker, who studied in Sydney as a younger man and has taken a special interest in me. He is a large person with a rugged flamboyance about him. I think to myself that he looks a bit like Eric Wareheim. He is in possession of an excellent baritone voice, and though his words are affected by the same circling as the others, he seems to deliver them with somewhat more confidence. Allen is the type of man to call a garden implement a garden implement, and do so with performance. At some point in the night I mention he would have made a good opera singer. He is holding court outside the bar, composing booming sentences about BREXIT, at my request and with very little filigree. He is pragmatic; though he had voted REMAIN, he doesn’t see it as the end of the world.

“We’ll have to wait and see, won’t we. There’s no reason to be alarmed at what is happening now economically – that will all blow over. It’s how things are managed in the long term, whether we can keep London as a financial centre. Trade could definitely take a hit if we don’t watch out.” He addresses all this to his pint of Guinness, which he holds resting flat on his outstretched palm, his fingers curled up to touch the sides, like an actor might hold a skull.

“There’s no reason to be alarmist; we’ve always been safe here. People are acting like we’re not part of Europe anymore, which is absolutely mental, of course. Paris is still a flight away, so is Prague. Even Bulgaria – if that’s your sort of thing.” I don’t ask him what he means.

Allen puts his Guinness down in order to light a large Polish cigar. Once it is going nicely, he picks up his glass, and in a moment of spontaneous passion (which is very Allen) throws back his head and exclaims “To the EU!” His voice rings deep, and the crowded outside section of the bar echoes the cheers. They raise their glasses in unison, though do so slowly, like a group of soldiers might raise a tattered flag.

Allen winks at me, and when he puts his beer back down it catches the edge of a paper coaster which is sent over the edge of the table. It bounces off one of the legs, under the rope demarcating the outside area, and (being circular) begins a racing roll over the cobblestones, down the hill away from the bar. Eventually, it reaches a cross-street some one-hundred meters away, and (almost imperceivable now) rolls under an iron fence and into a dense bush, lost forever. All the while my companion follows its journey closely, wearing an expression that is a curious mix of bewilderment and optimism. It seems to sum the whole thing up.

Words by Harry Peter Sanderson

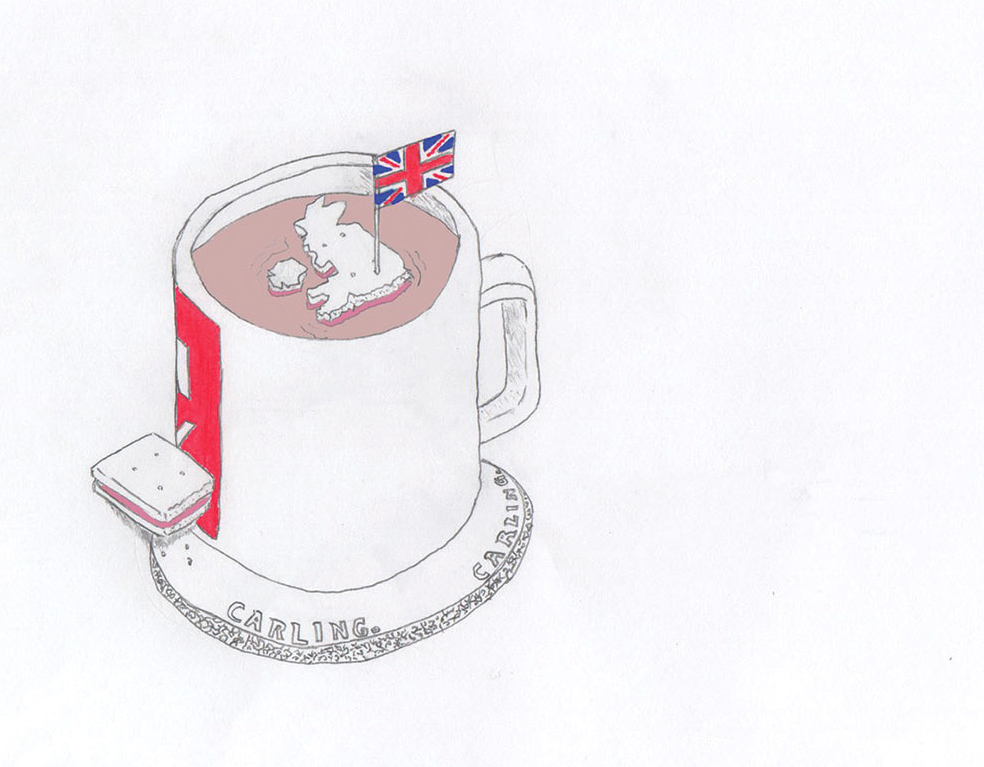

Art by Nathan Shaw