The world changed forever in 1973. Within the smoke and vibrations of a Bronx apartment building’s rec-room, at what is now known as the ‘Bethlehem of hip hop’ (1520 Sedgwick Avenue), young African-American and Latinx partygoers bobbed their heads and ‘breaked’ to the exhilarating and blended sounds of the ‘Father of Hip Hop’ DJ Kool Herc’s musical innovations. Made possible by Herc’s ground-breaking ‘Merry-Go-Round’ technique, (the method of using two turntables and a mixer to extend the instrumentals of classics such as James Brown’s “Give It Up or Turn Ita Loose”), emcees rapped over instrumental breaks while b-boys and b-girls breakdanced on the floor – sending the crowd into ecstasy.

Hip Hop was born.

Emerging from a generation that grew up marching with their elders and Martin Luther King during the Civil Rights Movement. Arisen from a collective that swayed their bodies to the healing oscillations of Gil Scott-Heron, Nina Simone, Marvin Gaye, and Aretha Franklin. Conceived from a people who organised the revolutionary Black Panther Party in the footsteps of Huey P. Newton, Bobby Seale, and Malcolm X.

Hip Hop was never going to be devoid of spirit.

It was pre-ordained that hip hop would go on to become one of the most commanding and controversial cultures of the last five decades – let alone a genre of music. In homage to an art-form, a philosophy, a nation, a force, and in the words of Nas, let’s “take a trip straight through memory lane” and reminisce about some of hip hop’s greatest protest anthems.

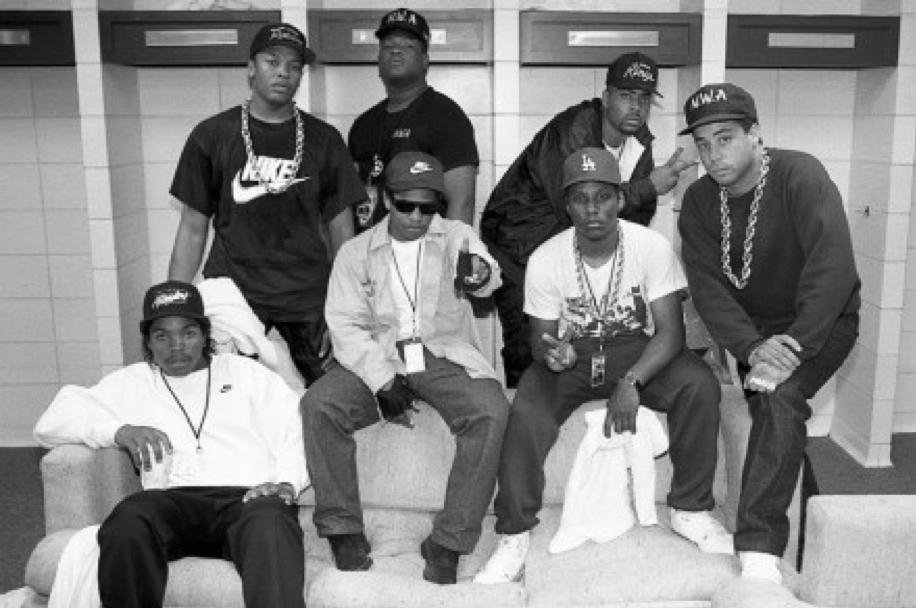

“Fuck tha Police” – N.W.A., Straight Outta Compton, 1988

Upon its release, Australia’s own triple j was the only radio station in the world to play N.W.A.’s most controversial hit, “Fuck tha Police”. After six months of air time, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation banned the song after a complaint from a Liberal Party Senator, thus marking the beginning of many objections regarding “Fuck tha Police”‘s subject matter. Even the members of N.W.A. themselves, Ice Cube, Eazy-E, Dr. Dre, Arabian Prince, DJ Yella, and MC Ren, were arrested for performing the revolutionary masterpiece at their own concert in Detroit:

They put out my picture with silence

‘Cause my identity by itself causes violence

The E with the criminal behaviour

Yeah, I’m a gangsta, but still I got flavour.

For the gangsta rap supergroup, who had grown up in the low socio-economic area of South-Central Los Angeles during the 1980s era, “Fuck tha Police” was the inevitable and justified byproduct of a demographic (African-American and Latinx youth) who had witnessed and experienced high levels of police brutality and harassment. Regardless of the song’s polarising reception, from concerned parents to self-defined ‘good’ cops, “Fuck tha Police” has only grown stronger as a highly personal and politicised response to the continuous violation of the physical, psychological, and socio-economic position of targeted minority groups in the United States. In Ice Cube’s own words, “we wanted to highlight the excessive force and … the humiliation that we go through in these situations. So the audience can know why we wrote “Fuck the Police” and they can feel the same way.”

“Fight the Power” – Public Enemy, Fear of a Black Planet, 1989

Straight-forward, pithy, and unyielding, “Fight the Power” is the ultimate protest anthem. Public Enemy’s highly influential hit borrows samples from a plethora of well-known black musicians and groups such as The Isley Brothers, The Dramatics, and James Brown – all of whom are routinely sampled within hip hop’s broader discography. “Fight the Power”‘s versatile ‘sample portfolio’ of celebrated black musicians is mirrored in the song’s passionate music video, paying tribute to a range of revered black activists and leaders including Marcus Garvey, Angela Davis, and Frederick Douglass. The music video’s repeated foregrounding of black musical and socio-political icons can be interpreted as merely a montage of black excellence, but when understood in alignment with “Fight the Power”‘s brazen lyricism, the song’s socio-political implications are radically iconoclastic and transformative in the context of the United States:

Elvis was a hero to most

But he never meant shit to me you see

Straight up racist that sucker was

Simple and plain

Motherfuck him and John Wayne

Cause I’m Black and I’m proud

I’m ready and hyped plus I’m amped

Most of my heroes don’t appear on no stamps

Sample a look back you look and find

Nothing but rednecks for 400 years if you check

Filmed in Brooklyn and directed by Spike Lee, the music video presents Flavour Flav and Chuck D leading a march through the streets, complete with some protesters donning the sleek regalia of the Black Panther Party; black leather clothing with a matching beret. Notably, members of the crowd in the “Fight the Power” music video are of all racial backgrounds. While the track’s point of focus is undeniably centred on empowering and honouring black voices and perspectives, “Fight the Power” has become a staple tune within the genre of protest music – especially against authoritarian and oppressive governments. Chuck D’s persuasive baritone rhymes call for oppressed peoples around the world to become politically active and to unite and organise against the common enemy, while also alluding to Martin Luther King Jr.’s vision for a “Beloved Community”:

We got to pump the stuff to make ya tough

From the heart

It’s a start, a work of art

To revolutionize make a change nothing’s strange

People, people we are the same

No we’re not the same

Cause we don’t know the game

What we need is awareness, we can’t get careless

You say what is this?

My beloved let’s get down to business

“La Raza” – Kid Frost, Hispanic Causing Panic, 1990

“This is for la Raza.”

An ode to his Chicanx (Mexican/Mexican-American) culture, “La Raza” is the most well-known Chicanx hip hop track in the United States. With firme rolas (funky overlayed sampled music) from El Chicano and Graham Central Station, “La Raza,” which means ‘the people,’ combines pre-Columbian Mexican history and contemporary Chicanx culture by integrating Aztec iconography, street art, and lowriders to visually demonstrate the permanence and evolution of Chicanx people on their ancestral homelands. Additionally, Kid Frost’s enunciated Spanglish vocals and self-assured lyricism rejects negative, white-American constructions of Chicanx identity by smoothly re-asserting the warrior-like, enduring strength of Chicanx people – particularly in light of historical conflicts such as the Mexican-American War and the Zoot Suit Riots:

Vatos, cholos, you call us what you will

You say we are assassins and that we are sent to kill

It’s in my blood to be an Aztec Warrior

Go to any extreme and hold no barriers

Chicano and I’m Brown and I’m proud.

Standing the test of time, “La Raza” is an essential tune for demonstrating solidarity with Mexican and Chicanx people in today’s daunting age of Trump – and is also perfect for cruising around Southern California in a ’63 Impala!

“U.N.I.T.Y.” – Queen Latifah, Black Reign, 1993

“Who you callin’ a bitch?” the first lady of hip hop, Queen Latifah, authoritatively questions her audience. In the same vein as her legendary collaborative tune “Ladies First” with Monie Love, another fellow female emcee from the golden age of hip hop, “U.N.I.T.Y.” demands that women have a seat at the table of the hip hop nation. After all, it is no secret that hip hop has traditionally been dominated by stereotyped notions of masculinity – especially at the time of “U.N.I.T.Y.”‘s release. However, owing to the lyrical and representational foundations being laid by Queen Latifah and her contemporaries in the late 1980s and early 1990s, hip hop has undergone a steady shift towards giving female and queer identities a voice and platform within the discourse. Concurrent to hip hop lyrics that labelled women as decorative pieces, inherently beneath men, within the Madonna/whore complex, or that teased/overtly referenced violence against women (Ahem, “disregard females, acquire currency”), Latifah was spitting truths about sexual harassment and domestic violence whilst also advocating for self-defence and self-preservation:

That’s why I’m talking, one day I was walking down the block

I had my cutoff shorts on right cause it was crazy hot

I walked past these dudes when they passed me

One of ’em felt my booty, he was nasty

I turned around red, somebody was catching the wrath

Then the little one said, “Yeah me, bitch,” and laughed

Since he was with his boys, he tried to break fly

Huh, I punched him dead in his eye

And said, “Who you calling a bitch?”

[…]

But I don’t want my kids to see me getting beat down

By daddy smacking mommy all around

You say I’m nothing without ya, but I’m nothing with ya

A man don’t really love you if he hits ya

Accompanied by a mesmerising saxophone sample from The Crusaders’ 1972 track “A Message From the Inner City”, Latifah’s vocals alternate from a breezy chant for “U.N.I.T.Y.” to an earnest poetic conversation on the vernacular and attitudes of hip hop culture:

Instinct leads me to another flow

Every time I hear a brother call a girl a bitch or a hoe

Trying to make a sister feel low

You know all of that gots to go

The finished product can only be described as a feminist manifesto woven into a rhythmic mosaic.

“The Poverty of Philosophy” – Immortal Technique, Revolutionary Vol. 1, 2001

“My revolution is born out of love for my people, not hatred for others.”

A breakdown of the famous songs that make up hip hop’s activist repertoire would be incomplete without Immortal Technique. Despite the majority of Tech’s discography being militantly political, the underground rapper is most commonly known to mainstream audiences for his morbid warnings about the allure of gangsterism in his track “Dance with the Devil”. Released in the same album, however, is the profoundly analytical and subversive spoken-word speech that is “The Poverty of Philosophy”. Naming the song after a tract published in 1847 by Karl Marx, Tech (who is Afro-Peruvian) lectures about class consciousness as he critiques the devastating legacies of imperialism, racism, and capitalism, in the Americas and other colonised continents:

Latino America is a huge colony of countries whose presidents are cowards in the face of economic imperialism. You see, third world countries are rich places, abundant in resources, and many of these countries have the capacity to feed their starving people and the children we always see digging for food in trash on commercials. But plutocracies, in other words a government run by the rich such as this one and traditionally oppressive European states, force the third world into buying overpriced, unnecessary goods while exporting huge portions of their natural resources.

Alluding to the post-Columbian policies and events that enforced the tightknit relationship between colonisation, imperialism, and capitalism – i.e., the invention of ‘whiteness’ after Bacon’s Rebellion in order to discourage class-based camaraderie amongst indentured and enslaved white and black Americans in the colonies, Tech proposes that it is classism first, and racism second, that forms the nucleus of oppression in the Americas:

As different as we have been taught to look at each other by colonial society, we are in the same struggle and until we realize that, we’ll be fighting for scraps from the table of a system that has kept us subservient instead of being self-determined.

Let it not be mistaken that Tech is exceptionally in tune with race-relations in the Americas, as he articulates in many of his songs such as “Harlem Streets” and “Peruvian Cocaine“, but that his praxis for radical socio-political and economic progression is centred in defeating the class system and economic inequality:

My enemy is not the average white man, it’s not the kid down the block or the kids I see on the street; my enemy is the white man I don’t see: the people in the white house, the corporate monopoly owners, fake liberal politicians those are my enemies.

[…] In fact, I have more in common with most working and middle-class white people than I do with most rich black and Latino people. As much as racism bleeds America, we need to understand that classism is the real issue. Many of us are in the same boat and it’s sinking, while these bougie mother-fuckers ride on a luxury liner, and as long as we keep fighting over kicking people out of the little boat we’re all in, we’re gonna miss an opportunity to gain a better standard of living as a whole.

In line with Immortal Technique’s unofficial title as hip hop’s professor of sociology, politics, and economics, “The Poverty of Philosophy” is a guerrilla-academic classic that echoes Public Enemy’s call for united rebellion in “Fight the Power”. Viva la Revolucion!

“January 26” – A.B. Original ft. Dan Sultan, Reclaim Australia, 2016

In the words of Immortal Technique in “Reverse Pimpology”, “Even Aborigines in Australia bump me.” Like a domino effect, hip hop’s unwavering presence in African-American and Latinx cultures has also found a solid fan base in many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. With shared post-colonial histories in mass incarceration, slavery, state-sanctioned violence, and poverty, many budding Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander hip hop artists find a sense of mutual allyship in the unity that hip hop facilitates.

Although Australia’s introduction to hip hop and its widespread engagement with the genre occurred much earlier amongst Indigenous Australians than in Australia’s European-dominated popular culture, for the majority of the last two decades, the face of Australian hip hop has revolved around artists such as Kerser and the Hilltop Hoods.

It has only been in the latter half of the 2010s that hip hop by Indigenous Australian artists (i.e., Baker Boy) hit the mainstream. However, one group, in particular, A.B. Original, comprised of Briggs (Yorta Yorta) and Trials (Ngarrindjeri), have made controversial waves in the Australian music scene – and unsurprisingly at that. Notably, the duo’s track “January 26” qualifies as Australia’s greatest protest song of the 21st century across all genres. Why? “January 26” completely annihilates the legal and cultural narrative foundations of the colonisation of Australia – the legal fiction of terra nullius and its aftermath of genocide, theft, and forced removal. The act of creating and broadcasting content that shatters Australia’s cherished national identity takes guts – especially in light of historically apathetic sentiments for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander rights and wellbeing; “I turn the other cheek, I get a knife in my back / And I tell ’em it hurts, they say I overreact / So fuck that! (fuck that!),” as Briggs raps.

The rhythmic duo address the inherent absurdity in the notion that ‘Australia Day’ is an inclusive and festive day for all Australians, as opposed to a day of survival and invasion:

How you wanna raise a flag with a rifle

To make us want to celebrate anything but survival?

In clarifying the reasons for A.B. Original’s frustration, “January 26” calls into question the nation’s rationale for celebration by revealing the glaring juxtaposition of experiences and emotions that Indigenous Australians and non-Indigenous Australians face on the date. A.B. Original urge us to think and feel empathetically about the significance of what January the 26th represents and its severe repercussions on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and culture:

I remember all the blood and what carried us (I remember)

They remember twenty recipes for lamingtons (yum)

Yeah, their ancestors got a boat ride

Both mine saw them coming until they both died

Fuck celebrating days made of misery (fuck that)

White Aus still got the black history (that’s true)

When asked whether A.B. Original dropped “January 26” on the date on purpose due to increasing support for the Change the Date movement, Trials stated that track’s content discusses “very old issues” and that it’s all “old hat.” Briggs further exclaimed that “if anything, [A.B. Original] were late.” For a bit of context, January 26th was declared a ‘Day of Mourning’ in as early as 1938 by fellow Yorta Yorta man William Cooper and the Australian Aborigines League. The actual celebration of ‘Australia Day’ on January 26th as a national public holiday is only 25 years old, beginning in 1994. Something tells me that for Australia, “January 26” is only the beginning of what is to be an era of unapologetically pro-Aboriginal and anti-colonial music – and I can’t wait.

“Tomboy” – Princess Nokia, 1992 Deluxe, 2017

Who that is, hoe?

That girl is a tomboy!

That girl is a tomboy!

That girl is a tomboy!

As much as I remain stubbornly loyal to the hypnotic flows of old school boom-bap and g-funk, it’s only right to conclude this lyrical compilation on a contemporary note. Introducing, Princess Nokia; the quirky, versatile Nuyorican rapper/singer of Afro-Indigenous ancestry. Nokia’s hit “Tomboy” affirms the same sex-positive mantras of pioneering body-positive emcees such as Salt-N-Pepa and Lil’ Kim in the 80s and 90s, albeit with a more candid approach. Rejecting the male gaze and instead re-shaping sexual-bodily perspectives to reflect women’s and queer declarations of self-love, “Tomboy” flips the bird to society and hip hop’s hypersexualised and ultra-feminine conception of womanhood. In the music video, Nokia, who identifies as sexually-fluid and queer, illustrates the nuances of her identity by proudly partaking in typically ‘un-ladylike’ activities by dressing in baggy clothes, playing basketball, dancing on top of a car in the streets of New York, slurping noodles, smoking a blunt, wearing boxers, and calmly showing her breasts to a busy street full of traffic, a stark contrast to the video vixens who have traditionally draped male rappers in mainstream hip hop videos:

Who that? Who that? Who that? Princess Nokia, Baby Phat

I be where the ladies at, who know how to shake it fast

We gon’ spit that brazy track, you know that I’ll take it back

I’m spittin’ the illest mack Yeah, hoe!

Who that? Who that? Who that? Princess Nokia, make it clap

She with it to set it back and give ya the fire track

And just a warning… ‘Tomboy’ is ridiculously catchy, so don’t stress if you get stuck blurting out the song’s chorus in public:

With my little titties and my phat belly

My little titties and my phat belly

My little tittles and my phat belly

(That girl is a tomboy)

Instead, embrace it! That’s the beauty of the track – to shamelessly own and love what is yours.

–

When I say hip-hoppers, I mean black, white, Asian, Latino, Chicano, everybody. Everybody. Hip-hop has united all races. Hip-hop has formed a platform for all people, religions, and occupations to meet on something. We all have a platform to meet on now, due to hip-hop. That, to me, is beyond music. That is just a brilliant, brilliant thing.

~ KRS-One

Words by Eliza Huston

Feature Image Source: Raymond Boyd/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

A shortened version of this article appeared in Edition 5, Vol 90. of Pelican, HOPE. It is out and available now.