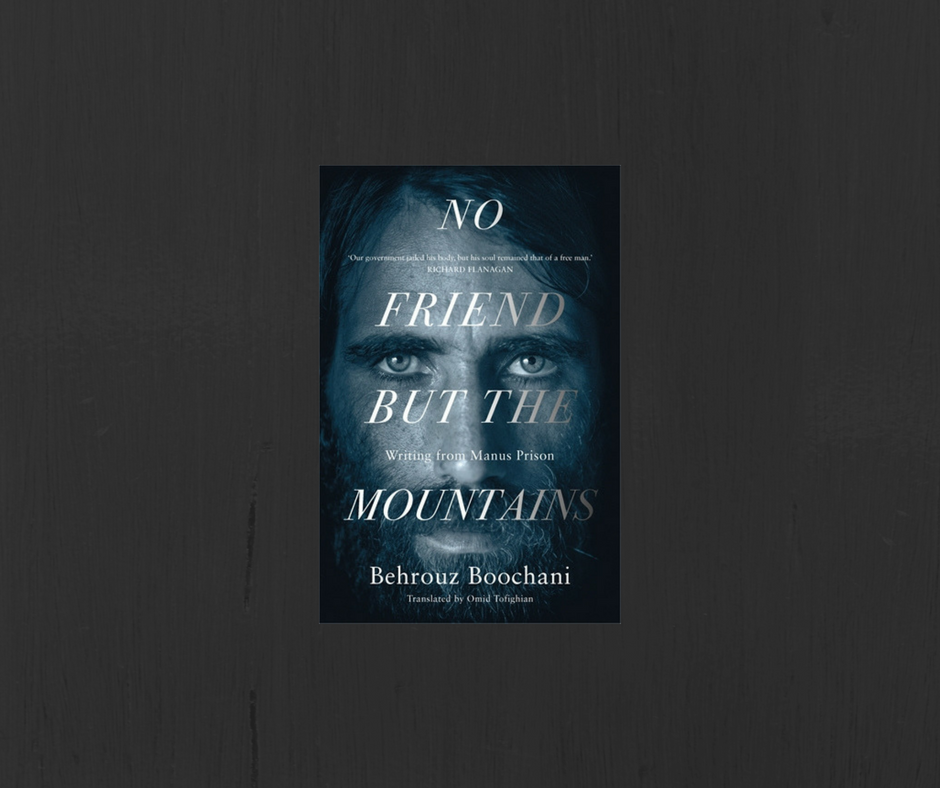

Behrouz Boochani’s newly released book No Friend but the Mountains is more than a refugee’s memoirs or a political opinion piece. In fact, it’s a book that resists classification. It’s the story of one man, what it means to be human, and what it means to be an artist. And since none of us ever truly fit into a category as people, it makes sense that our experiences can also not be easily classified.

The book tells the story of Boochani in his own words – his upbringing and youth in his home of Kurdistan, the harrowing travel by boat from Indonesia to Australia to escape persecution at the hands of the Iranian regime, and the debilitating conditions faced by the detainees inside Manus Island. Boochani includes beautiful poetry in the midst of his prose, adding an element of vivid horror and realism to the story. Sometimes seeing the images in his poetry brings his prose to life in a thoroughly haunting manner. With repetition that plays out like a rhythmic song, you can’t help but imagine what the book would have read like in its original Farsi, seeing as it was translated in English.

No Friend but the Mountains is in many ways an indictment of the border-industrial complex, and the role all of us play in it. It looks at the power structures that have allowed the Australian government to create a ‘detention facility’ that functions more like a prison, and the complicity that the Australian people have in allowing such a facility to exist. It examines media violence that exploits brutalised brown and black bodies, the way the Australian government has forced PNG national to become complicit in the running of the prisons, and the uncertainty of meaningful immigration outcomes for the prisoners.

Boochani’s lived experiences are sharpened to a point. He refuses to shy away from the most disgusting and painful experiences including describing self-harm, brutality from prison guards and medical officers alike, and the poor sanitation. It can be second nature to want to skip the more difficult portions of the book, but they are worth reading, even if just to remind yourself that while reading them might be difficult, someone has had to live through them.

At the same time, the book is also a testament to the academic and philosophical intelligence of Boochani, who has the capability of analysing his own experiences with the perspective of an outsider looking in. It can be difficult to understand the true scope of one’s situation while you are in it, however Boochani not only manages to analyse his experiences, but manages to do so through the concept of ‘Kyriarchy’ which is explained further in the translator’s notes at the end of the text. He also creates the Manus Prison Theory which examines how the kyriarchy functions within the prison to subjugate its subjects.

The book is eye-opening, and purely by being written by a voice with lived experience, dispels many of the myths about refugees that have proliferated our collective psyche. It does away with the story of irrational violent brutes, as well as of refugees being ‘good people’ who need to be saved. It shows them as they are – people. With flaws. People who make mistakes. People who fall victim to many vices including greed, jealousy, arrogance, and anger. But it shows them as people nonetheless. People who deserve to be given their human rights regardless of their behaviour. People who do not deserve to be treated like animals, brutalised or even killed.

Boochani does not use names often in his book. Instead, he describes people with titles that summarise their best or most defining qualities such as ‘The Gentle Giant’ or ‘The Boy With Blue Eyes’. While these titles do make the characters in the book universal, they also make them endearing. You grow attached to their stories. You see them through the eyes of Boochani, and not through the lens of the media or the government. Their stories are important and worth listening to.

No Friend but the Mountains is not an easy read. However, it is also not a book you can put down easily. It is a must read. It is an important and eye-opening read that every Australian needs to experience once in their lives.

No Friend but the Mountains can be found at all good bookstores.

Ishita Mathur | @ishitamathur7

Ishita has become addicted to mandarins in the winter.