Question: How much is our national identity worth? Or rather, how susceptible are ‘Australian values’ to serious examination? Sorry if these questions are vague or flimsy, but then again, Australians have pretty vague and flimsy ideas of what constitute national values. Who’s up for a thought experiment? A familiar dilemma within contemporary liberal democracies is the tenuous balancing act between liberty and security. The last 15 years have seen civil liberties gradually eroded (with public consent) in exchange for greater protection from terrorism; meanwhile lazy, comforting preconceptions about Islam and freedom and Western exceptionalism have been allowed to calcify without much notice or dissent. Is the exchange worth it? Suppose we chose to regard the detention of the 1,589 people in Nauru and Manus Island as an extension of this exchange? Suppose that by outsourcing the sacrifice of liberty to a third party, we could not only maintain our own security, but our liberty to boot? What effect would that choice have on our national character, if any?

These are some abhorrent and discomfiting suggestions. Maybe they explain why we’ve been reluctant to engage in a national conversation about our border policy – it’s simply not pleasant to talk about in great detail. Maybe we’re not capable of such a conversation. But consider this: reluctance to engage in public discourse effectively cedes the floor to the select few, allowing those with power to frame not just the conversation, but the very question itself. This was best demonstrated in the build-up to the 2013 federal election. There’s something to be said for how quickly and expertly the political class framed the discourse on immigration and asylum seekers, once they realised its political potential. Labor and the Coalition openly competed to offer the most brutal border protection policy going, reducing a complex (yet manageable) issue to a simplistic three word slogan. You know the one. Insidious usage of language played not only on deep-rooted xenophobia, but the Australian obsession with the ‘fair go’. Suddenly the desperate and vulnerable are crudely recast as ‘illegals’, ‘boat people’, ‘queue jumpers’. Even the term ‘asylum seeker’ has become loaded with connotation.

By excusing ourselves from having an adult debate on immigration, are we committing a sin of omission? We’re certainly placing a lot of trust in our political class. Do we trust our elected representatives to uphold our values? What are the effects on the Australian character of places like Nauru and Manus Island; the conduct and competence of G4S and Transfield Services and Wilson Security, who are employed by our Government; the brutal death of Reza Barati, struck in the head with a stick protruded by nails; the denial of basic sanitary items to female detainees; the denial of regular psychiatric care to detainees who have suffered torture, rape and solitary confinement; the denial of an abortion to a 23 year old Somali woman raped on Nauru? Can we trust that our values are being upheld in an atmosphere cloaked in secrecy and paranoia, and utterly lacking in transparency and due process? Consider that the newly established Border Force will not be required to disclose its “operational matters” to the public. Consider that the Australian Federal Police have been called to Nauru to investigate allegations of whistle blowing six times, and yet they have not been called to investigate sexual violence perpetrated against detainees. Consider that under the Migration and Maritime Powers Legislation Amendment 2014 an immigration officer’s primary duty is to remove a person without a visa “as soon as reasonably practical”, regardless of whether their claims have been properly assessed. Consider that this means asylum seekers can be returned to a country where they are likely to be persecuted and killed. Consider that 93 of the people held in detention on Nauru are children.

In the 60s, journalist Donald Horne coined an expression to describe Australia as he saw it: the lucky country. Through the 80s and 90s this came to be an endearing and self-congratulatory phrase with thoroughly conservative overtones, referring to everything from the weather to our national character to our economic prosperity. Life’s pretty great, no need to worry. The thing is, Horne never meant it as a compliment. Australia’s success is literally predicated upon good fortune, both mineral and geopolitical. An abundance of natural resources, along with an inherited Westminster political system and relative geographical isolation from global conflicts has incubated us from some harsh truths: that our stability was bequeathed to us, and our wealth was stolen from the people who were here first. As Horne puts it, Australia is a country “still [using] colonial blinkers”. We can’t believe our own luck, so we choose not to.

We’re very quick to tie this good fortune into our collective national identity, because it reinforces the notion that we succeed because of something inherently good in being Australian. Funnily enough, Horne’s hypothesis hinted that our good fortune would eventually render us too stupid to properly recognise or understand it. Think about that the next time somebody says, “she’ll be right”. Even more ironic is that our tendency to self-identify as a welcoming, tolerant and egalitarian society is likely a pretty powerful selling point to people hoping to come to this country.

“Have we become so selfish and frightened that we don’t even want to think about whether some things trump safety? What kind of future does that augur?”

Words By Matt Green

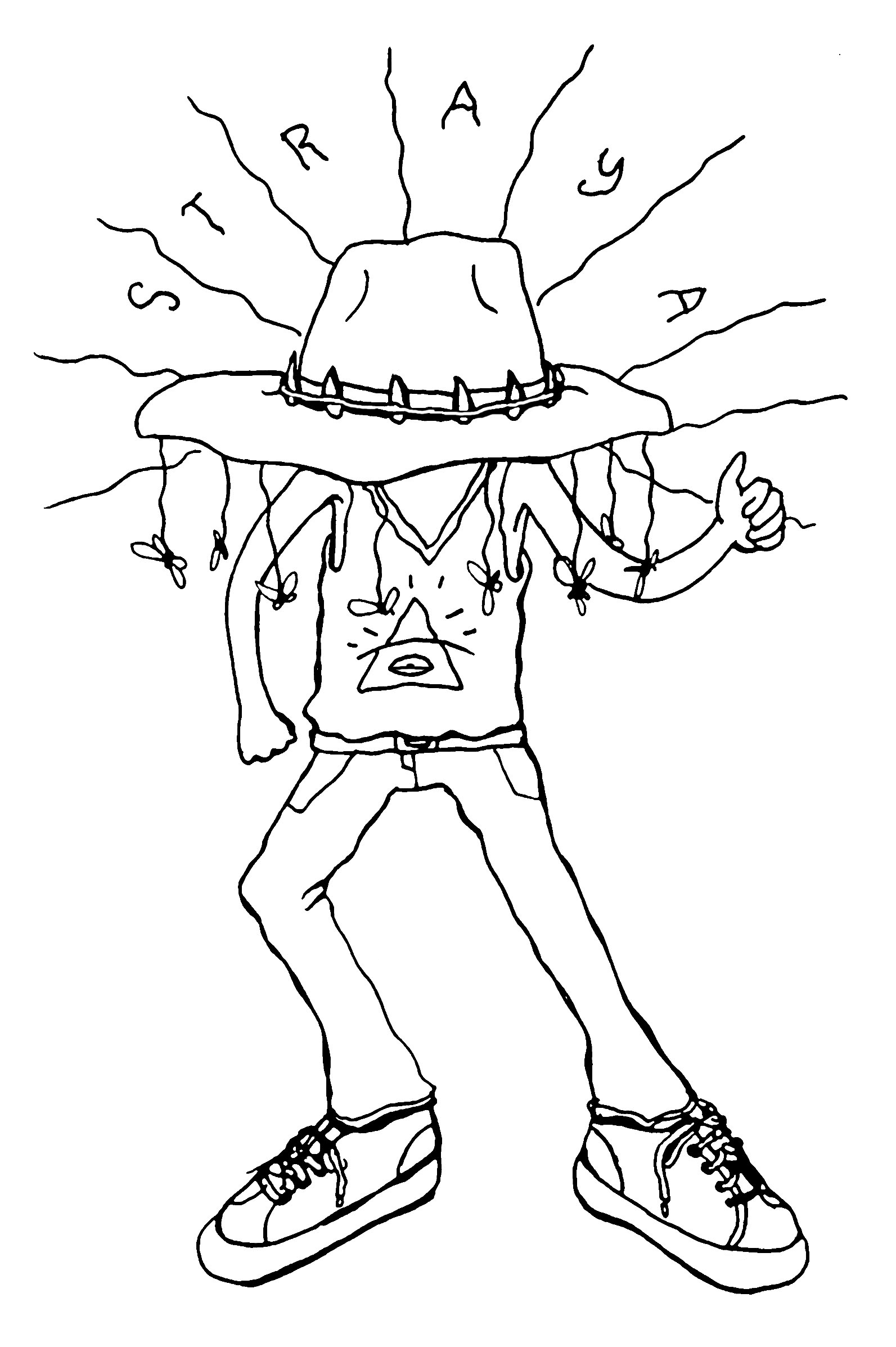

Art By Kate Prendergast