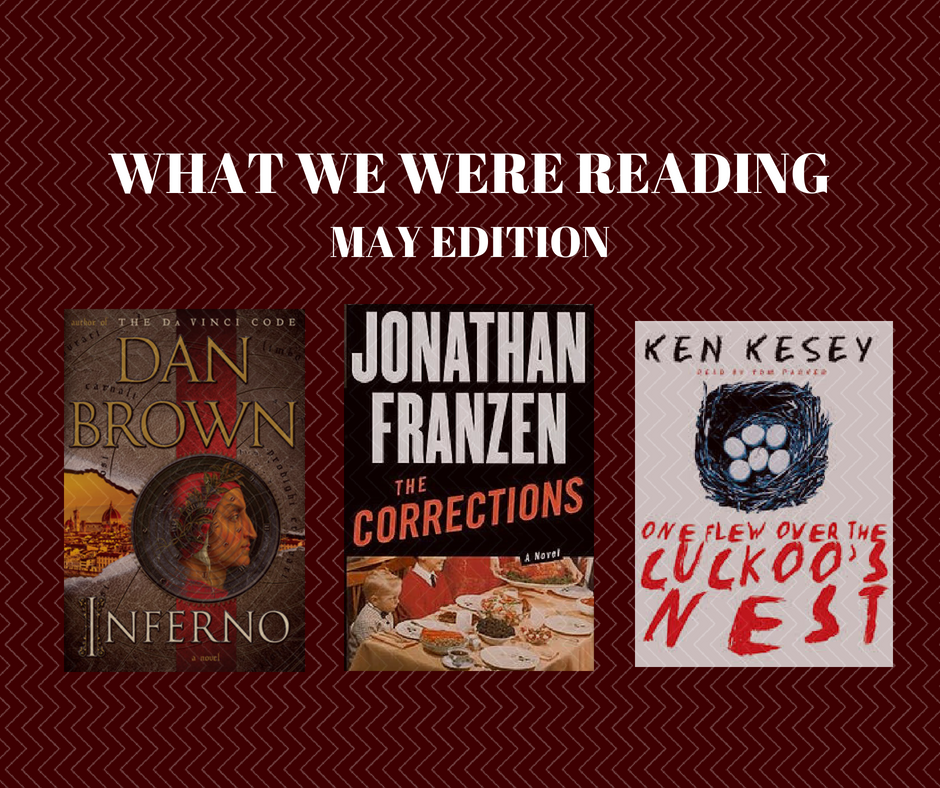

Inferno – Dan Brown

“The decisions of our past are the architects of our present.”

Published in 2013, Inferno is Dan Brown’s fourth novel following Harvard professor Robert Langdon. As in all the novels, Langdon decodes and analyses famous artworks and symbols to unravel evil plots and government conspiracies. The novel begins with an amnesiac Langdon and instantly introduces the compulsory femme fatale in Dr Sienna Brooks. In the Robert Langdon series, whether American, French or Italian, there is always a beautiful, heteronormative, child genius ready to help Langdon in his pursuit of the truth. This novel is no exception, as Brooks joins Langdon to stop a mysterious green eyed man in the streets of Italy. Inferno, a reference to Dante’s Inferno, uses the famous text as clues throughout the novel, instantly engaging the ancient Roman historians among us. Unfortunately for us non historians, Brown’s book falls painfully short of good, with predictability and cliché ripe on every page. In a last ditch effort to seem original Brown introduces a mind shatteringly ridiculous fuck you to the reader, also known as a ‘twist’. If this is your first Brown novel, go for it, have fun. But as someone who has read his other work, I found this novel, bland, convoluted and not up to his usual standard.

Cameron Carr

The Corrections – Jonathan Franzen

The Corrections centres on the extremely dysfunctional Lambert family, once a model of the Midwestern ideal of a nuclear family, now an estranged, embittered unit of people barely held together by blood relations. More specifically, The Corrections is about all of the ways that the Lamberts cope with Alfred Lambert’s (the patriarch of the family) Parkinson’s disease and worsening dementia, as well as each Lambert’s own personal failures. The “set up” on the back of the paperback I own, is that Enid Lambert (the matriarch of the family) attempts to get the family back together for Christmas one last time. This is a disservice to Franzen’s prose, because it sounds a bit like a wacky situation for a Christmas themed Hollywood comedy, and this is by no means a comedy, occasionally humorous though it may be.

This novel is about a failure of the American middle class ideal. There is a palpable sense of doom, that the ideal of life in Middle America, this identity, deeply flawed as it may be, is dying, and that the world outside has long passed it by.

The plot also contains dystopian elements, two miracle medical technologies: The first, a treatment offering “corrections” to aberrant behaviours by altering brain chemistry proposed to treat Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s, but also implied to be able to “correct” criminal or depressive moods. The second, a universal wonder-pill named Aslan that resolve people of their sense of shame. Both in turn threatening to remove the American populace at large of their individuality and personality.

Eamonn Kelly

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest – Ken Kesey

“But he won’t let the pain blot out the humor no more’n he’ll let the humor blot out the pain.”

Focusing on mental health wards in the early 60s, Kesey made huge strides in raising awareness of the brutality endured by the helpless interned at the time. Electrotherapy and waterboarding, are some of many examples of ‘treatment’ implemented in the 60s, and were largely considered an unsavoury and taboo topic. Kesey focuses on two characters; an incarcerated Native American and a loose-tongued larrikin famously portrayed by Jack Nicholson in the film of the same title. The novel also famously establishes the stereotyped sadistic nurse in the form of the infamous Nurse Ratched. The novel’s style is intentionally over dramatised and exaggerated , likely to mimic ‘the fog’ of mental illness the narrator experiences. As uplifting as it is tragic, One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest takes an in depth look at power relations in society. Between the warring factions of the hospital ward, many of the patients experience internal turmoil of their own. The novel contains several key messages, from self-empowerment to seeking guidance, culminating in a masterpiece of camaraderie, loyalty and loss.

Cameron Carr