Georgiana Molloy Anglican School in WA’s south-west courted controversy with a proposal to remove certain works from its Year 11 and 12 English courses. In an email sent to parents in early February, Principal Ted Kosicki criticized his school’s English reading lists as “abhorrent,” “uncensored,” and “crowded with inappropriate material.”

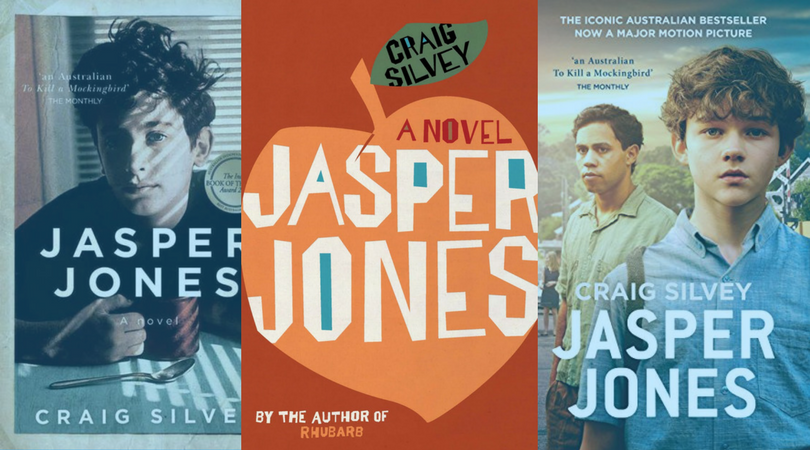

Mr. Kosicki suggested that the school had received parental complaints about the suitability of Craig Silvey’s Jasper Jones and Nam Le’s The Boat as high-school English texts. He also alleged that “vulgar language” and “explicit sexual innuendo” present in the works motivated his decision to remove the works from the curriculum.

Mr. Kosicki initially apologised to students who had read the works in preparation over the summer, indicating the school’s intention to cease teaching the books this year. Other works under scrutiny included Tim Winton’s Cloudstreet and Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet.

The school has since backpedalled on its decision in the face of pressure from prominent Australian literary figures and outcry within the national media. Mr. Kosicki noted in a follow-up statement released in the wake of the controversy that, “no texts on this year’s English list will be changed.”

Responding online, Craig Silvey thanked Principal Kosicki for “seeing reason,” and acknowledged those “who [had] voiced their support for the rights of our students to read challenging texts, and the rights of teachers to guide them.”

With the controversy dying down, Craig Silvey kindly agreed to speak to Pelican Magazine’s Michael Smith about free-speech, the book ban, and the importance of introducing young adults to challenging ideas through literature in schools.

Following the adage “any book worth banning is a book worth reading.” As an author, is having your work banned in some sense a badge of honour?

I’m not sure that I’m especially proud to learn that a ban of my work had been proposed, but I do want my books to provoke and challenge and inspire discussion. Obviously this requires a range of responses to a text – some of them complimentary, others more hostile. But so long as a passionate dialogue has been ignited, then a novelist, in part, has fulfilled their task. Good books ask questions, and their relevance is defined by the ongoing debate for answers.

Let me just say that I’m principally opposed to censorship. And I don’t just apply that philosophy to works that I support or admire. With the exception of cases of hate-speech, vilification, incitement of violence or restrictions designed to protect children, no work of art or opinion should ever be combatted by removing it from view or deeming it unlawful, particularly on the grounds that it is disagreeable, offensive or in breach of community standards.

The current controversy has provoked a whirlwind of attention surrounding both you and your work…Do you find it uplifting or frightening to have so many people willing to fight on your behalf?

I’m not sure if people were fighting on my behalf, so much as they were arm in arm, vocalising their opposition to censorship and the stifling of ideas. And that was really heartening.

What would you say is ‘inappropriate,’ about Jasper Jones, Cloudstreet, The Boat or Romeo and Juliet? Why do you think some parents and senior admin staff of GMAS were scared of these texts?

I can’t speak for the other texts which were under review, but my understanding is that their opposition to Jasper Jones stemmed from its language, adult themes, and depictions of violence.

What do you think makes appropriate reading material for students in a contemporary world where they have access to inappropriate material whenever they want it, thanks to the internet? Should schools deliberately present challenging or confronting material to students as a part of their curriculum?

I believe it’s part of the mandate for English departments to introduce challenging material to their middle and senior students, and to do so in a way that curates the discussion by providing social context and guiding the discussion and interpretation of these works. The classroom is critical in the process, because it’s often when students are introduced to these ideas in isolation that they can often be misunderstood.

This week marks the tenth anniversary of the apology to the stolen generations. The gap is only widening between Aboriginal and white Australia, why is it now more important than ever for students to be exposed to texts like Jasper Jones?

I’m not sure it’s more or less relevant now, particularly in the case of students, because each year brings a new wave of people on the cusp of adulthood who are often just beginning to broaden their perspectives and expose themselves to wider issues and ideas – so it will always be important, regardless of the social urgency outside the classroom.

There is a line in Jasper Jones that says Corrigan is a town of barnacles that “clench themselves shut and choose not to know,” about the outside world. Do you find any eerie parallels between the potential book ban in this small regional WA town and some of the plot of Jasper Jones?

To a degree. Look, I empathise with these parents, who have a particular belief system, and whose first instinct is to protect their children. However, it’s ultimately a disservice to shield young adults from truths that are upsetting, because it’s inevitable that they will eventually encounter them. We often lie to young children about the truth of the world because they’re not equipped to understand it. Part of what it means to become an adult is to burst the protective layer of your childhood and look beyond yourself, which permits you perspective and empathy and humility. Some people never go through that process, and in doing so, never really grow up. This is actually what Jasper Jones is ultimately about.

Michael Smith | Education Editor

Michael is a fan of ducks and thinks hummus should be its own food group.